Color Wheel of Friendships..!!

Happy Friendship Day Sunday of 3 Aug 2025.

By Author VATs(69)_ayana

From GRP “Aham tvam SuMitrasmi” – I & You Are Good Friends for good life..!!!

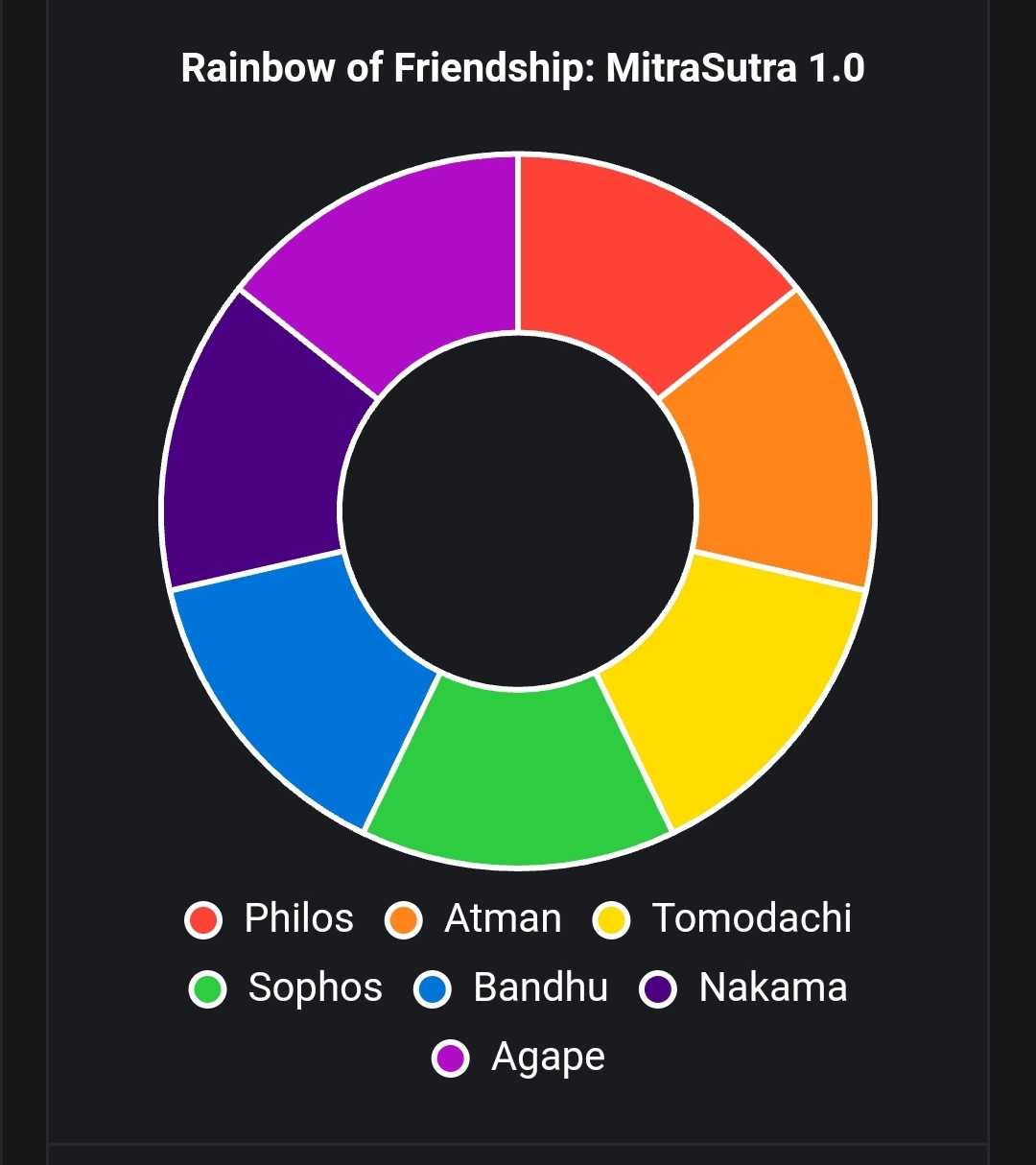

Friendship, a vibrant tapestry woven from the threads of human connection, colors our lives with joy, wisdom, and meaning. Drawing from the rich philosophical traditions of Greek, Indian, and Japanese thought, the MitraSutra 1.0 presents a spectrum of friend types that illuminate existence, each contributing a unique hue to the rainbow of friendship. “Mitra,” meaning friend in Sanskrit, and “Sutra,” meaning a thread or aphorism, combine to form a guide to the art of companionship.

Dedication: This MitraSutra is lovingly dedicated to all our friends, from age 1 year to today, who have shared boundless fraternal love, care, and good times on path of life. If this msg reaches you, know it’s for you, My Mitra! From my first best buddies—Arun at Baba Nursery, Banu at St.Annes & Vasanth Nagar, to Manjesh & all at Florence Basaveshwaranagar, to all buddies at Lowry & KR Puram, Cathedralites, MSRITians, DM+IIScians, BLCians, TechMitys, Toastmasters, DSUites, Bengalureans, Hyderabadis, LOLians, Architects, Designers, Men’s & Fathers’ Rights Activists, Bengaluru Advocates, all our Pan Indian GRouPers, and many more good Mitras—you are remembered and thanked. I feel grateful for your presence as friends, making this life worth living and loving you all for the companionship and various types of FRIENDSHIPs we shared, are Sharing & Will Share.

Oh My Mitra, a Trustable Saathi on Jeevan Yatra!!

Oh nanna Gelaya, Endu neenu nana manasaliiruve nennapanthe, Hrudaydali hariyuve rakthadanthe, Namma sneha shasvatha, bareyalu e-jeevana grantha.

Oh Mere Dost, Tum mere dil me hamesha base’ho, har bill ko mein hi barunga, har muskil mein jo tum saath they bhai ho ke.

Oh En Nanbane, nee’than en balam, nee’than en aram, nee’than en manam, nee’than en Adhaaram.

Oh Mitruda, Noove na Dhairyam, Noove na Madhuram, Noove naku sthiram even without Rum..

Oh My Friend, Know Our Relationship has no End, Whatever our situations may move us apart, Know that you always were, are and will be in this friend’s heart.

Thanks for Being a Friend, I am ever indebted to Your Friendship & Faith.

– Your Dear Friend G.R. Guru Prasad.

The Spectrum of Friendship

1. The Philos (Greek: Love and Affection)

Color: Red (Passion and Warmth)

Inspired by Aristotle’s concept of philia—friendship rooted in mutual affection and shared virtues—the Philos is the friend who radiates warmth and loyalty. They celebrate your victories as their own and stand by you in storms. This friend embodies the Greek ideal of a bond that fosters personal growth through love and trust.

Example: The friend who stays up late to listen to your heart’s troubles, offering comfort without judgment.

MitraSutra Aphorism: “In the embrace of Philos, hearts align like stars in a constellation.”

2. The Atman (Indian: The Soul-Companion)

Color: Orange (Vitality and Connection)

Rooted in Indian philosophy, particularly the Upanishadic concept of Atman (the true self), the Atman friend sees and nurtures your innermost essence. They guide you toward self-realization, reflecting the Bhagavad Gita’s emphasis on selfless companionship as a path to dharma. This friend is a mirror to your soul, encouraging authenticity and spiritual growth.

Example: The friend who asks, “What does your heart truly seek?” and listens deeply to your answer.

MitraSutra Aphorism: “The Atman friend is a lamp, illuminating the path to your own truth.”

3. The Tomodachi (Japanese: Harmony in Presence)

Color: Yellow (Joy and Serenity)

Drawing from Japanese Zen and the concept of wa (harmony), the Tomodachi is the friend who brings peace through their presence. They embody the quiet strength of shared silence and mutual understanding, as seen in the Japanese value of omoiyari (empathy and consideration). This friend creates moments of joy without demanding attention.

Example: The friend with whom you can sit quietly by a river, feeling complete without words.

MitraSutra Aphorism: “In the stillness of Tomodachi, two hearts breathe as one.”

4. The Sophos (Greek: The Wise Guide)

Color: Green (Growth and Wisdom)

Inspired by Plato’s vision of friendship as a pursuit of truth, the Sophos is the friend who challenges your ideas and sparks intellectual growth. They engage in Socratic dialogue, pushing you to question assumptions and seek wisdom. This friend is a mentor and co-explorer in the journey of knowledge.

Example: The friend who debates life’s big questions with you over coffee, leaving you wiser.

MitraSutra Aphorism: “The Sophos plants seeds of thought that bloom into understanding.”

5. The Bandhu (Indian: The Kin of Heart)

Color: Blue (Trust and Depth)

From the Indian concept of bandhu (connection or kin), rooted in Vedic philosophy, this friend is family by choice. They embody the trust and loyalty of Rta (cosmic order), offering unwavering support through life’s cycles. The Bandhu is the friend who feels like home, no matter where you are.

Example: The friend who shows up at your door with soup when you’re sick, without being asked.

MitraSutra Aphorism: “The Bandhu weaves a bond stronger than blood, rooted in the heart’s truth.”

6. The Nakama (Japanese: The Comrade of Purpose)

Color: Indigo (Unity and Purpose)

Inspired by the Japanese concept of nakama—a group united by shared goals and loyalty—the Nakama is the friend who walks beside you in pursuit of a common dream. This reflects the Japanese value of collective harmony and dedication, as seen in stories of samurai loyalty. They inspire you to strive for something greater.

Example: The friend who joins you in a creative project, pushing you both toward excellence.

MitraSutra Aphorism: “With Nakama, the path to purpose is never walked alone.” not Nikamma (In Urdu means Useless)

7. The Agape (Greek: The Selfless Beacon)

Color: Violet (Compassion and Transcendence)

Rooted in the Greek notion of agape—unconditional, selfless love—the Agape friend loves without expectation. They embody the Platonic ideal of love that transcends personal gain, offering compassion that uplifts and heals. This friend sees the divine in you and loves you for it.

Example: The friend who supports you through failure, asking nothing in return.

MitraSutra Aphorism: “The Agape shines like a star, guiding without demanding.”

The Rainbow’s Essence

Together, these friends form the Rainbow of Friendship, each type contributing a distinct color to the spectrum of human connection. From the passionate loyalty of the Philos to the selfless compassion of the Agape, the vibrant joy of the Tomodachi to the soulful depth of the Atman, these archetypes draw from Greek, Indian, and Japanese wisdom to remind us that friendship is a universal art. The MitraSutra 1.0 invites you to cherish these connections, for they make life’s canvas vibrant and complete.

Author’s Note: May the MitraSutra inspire you to seek, nurture, and celebrate the friends who color your world.

VATs(69Mitra)_yana, on behalf of GRP “Aham tvam SuMitrasmi”

Bibliography for MitraSutra 1.0: The Rainbow of Friendship

Below is a list of references that inspired the philosophical foundations of the MitraSutra 1.0, drawing from Greek, Indian, and Japanese thought to conceptualize the seven types of friendships.

- Aristotle. (350 BCE). Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by W. D. Ross, 1925. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Source for the concept of philia (friendship based on mutual affection and virtue) and agape (selfless love), informing the Philos and Agape friendship types.

- Plato. (360 BCE). Symposium. Translated by Benjamin Jowett, 1871. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Provides insights into the pursuit of truth and wisdom through dialogue, shaping the Sophos friendship type.

- Bhagavad Gita. (circa 2nd century BCE). Translated by Eknath Easwaran, 2007. Tomales, CA: Nilgiri Press.

- Influences the Atman friendship type through its teachings on self-realization and dharma in companionship.

- Rig Veda. (circa 1500–1200 BCE). Translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith, 1896. Benares: E. J. Lazarus and Co.

- Source for the concept of bandhu (connection or kin) and Rta (cosmic order), foundational to the Bandhu friendship type.

- Suzuki, D. T. (1959). Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Informs the Tomodachi friendship type with the Zen concept of wa (harmony) and omoiyari (empathy).

- Murasaki Shikibu. (11th century). The Tale of Genji. Translated by Royall Tyler, 2001. New York: Penguin Classics.

- Provides cultural context for the Nakama friendship type, reflecting Japanese values of loyalty and shared purpose.

- Upanishads. (circa 800–400 BCE). Translated by Juan Mascaró, 1965. London: Penguin Books.

- Shapes the Atman friendship type with the concept of the true self (Atman) and its role in spiritual connection.