The IndoFamily System is a nurturing fellowship for intergenerational Indians through spread of Moral and Ethical Values across Ages..

After the modern phenomenon of Globalization & Native Cultural Colonization & corruption.. We now see family Honor and Harmony is replaced by greed for money and Cancer of Body and mind, here are many cases where child abuse, spouse abuse and parental abuse is seen in Indian Families..

Indian Values of Matha, Pitha, Guru aur Deva is replaced by Valuation of Money, Property, Gaadi aur Deviance_Divorces…

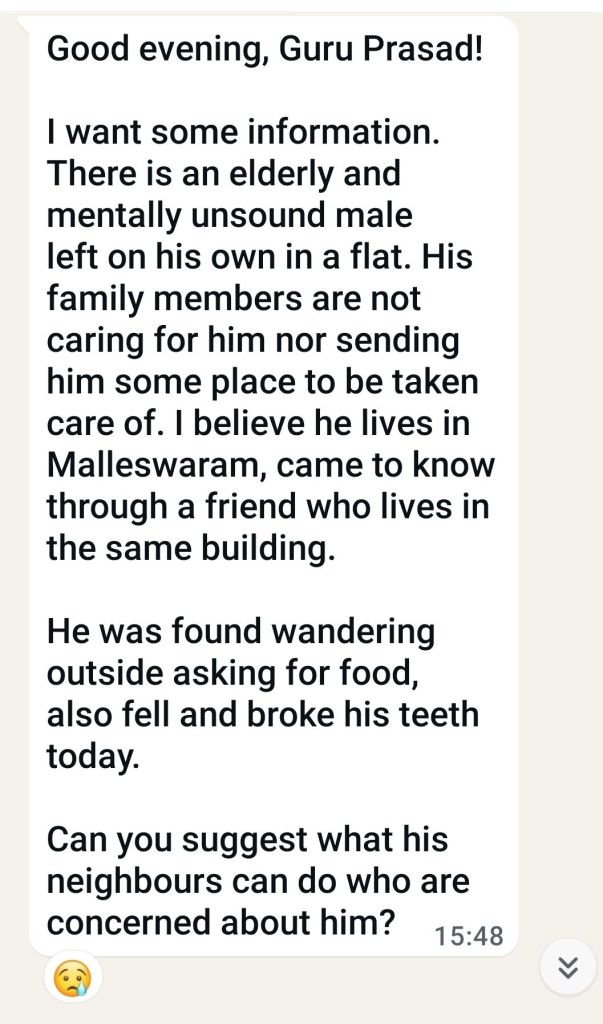

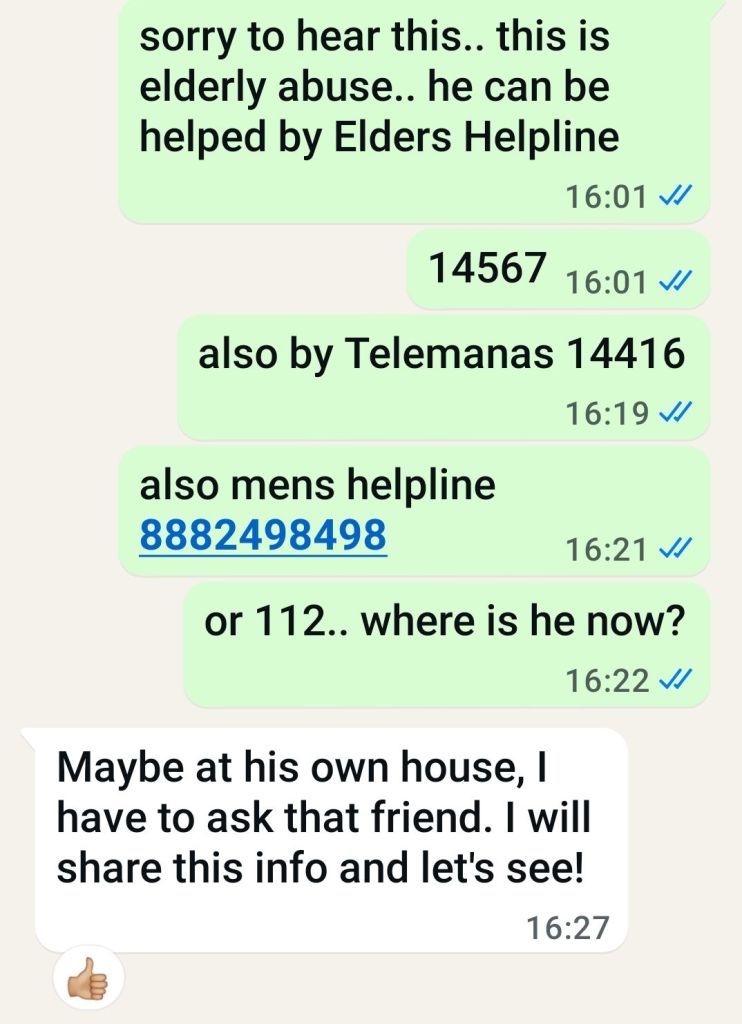

This Post address the recent trend of elderly abuse.. though there is a senior citizens act many parents are abused by their children. here are resources for protection and prevention of Elders Abuse.

- Cases.. in cities eg.. Bangalore..

Received message From a Concerned Empathic Friend of elderly.

2. Causes.. The influence of lovers or abusive In laws and young children themselves becoming Radicalized by Anti-family & Selfish_Sexish Ideologies.. Greed for property and materialism..

3. Remedies Elderly Helplines, Psychological Resources and Legal recourse.

DLSA Helpline can also be contacted at 15110

https://x.com/ImtiazMadmood/status/1940440341582094341

A police Compliant can be registered and action taken remedies given by govt from the children or legal heirs of the neglected elder.

*Swiss Time Bank*

A student studying in Switzerland

observes:👇

While studying in

Switzerland,

I rented a house near the school.

The landlady Kristina is a

67-year-old single

old lady who had worked as a teacher in a secondary school before she retired.

Switzerland’s pension is

very good, enough to not worry her

about food and shelter in her later years.

However, *she actually found “work” – to take care of an 87-year-old single old man*.

I asked if she was

working for money.

Her answer surprised me: “I do *not work for money*, but I put my time in

the *time bank*, and

when I cannot move in my old age,

*I could withdraw it*.”

The first time I heard about this concept of “time bank”, I was very

curious and asked

the landlady more.

The original “Time Bank” was an old-age pension program developed

by the Swiss Federal Ministry of Social Security.

People saved the

time taking care of

the elderly when

they were younger, and when they were old, ill or needed care could withdraw it.

Applicants must be healthy, good at communicating

and full of love.

*Everyday they have to look after the elderly who need help*.

*Their service hours will be deposited into the personal time accounts* of the social security system.

She went to work twice a week, spending two

hours each time helping the

elderly, shopping, cleaning

their room, taking them out to sunbathe,

chatting with them.

According to the agreement, after one year of her

service, *Time Bank* will calculate her working hours and issue her

a *time bank card*.

*When she needs someone to take care of her,*

she can *use

her *time bank card* to time to

*withdraw* *time and time interest”*. After the information

verification, *“Time Bank will assign other volunteers to take care of her at the hospital or her home.*

One day, I was in school and the landlady called and said she fell

off the stool when

she was wiping the window.

I quickly took leave and sent her to the hospital for treatment.

*The landlady broke her ankle and needed to stay in bed for a while*.

While I was preparing to

apply for a home to take care of her,

the landlady told me that I need not worry about her.

*She had already submitted a withdrawal request to the “Time Bank”.*

Sure enough, in less than two hours “Time Bank”

*sent a nursing/volunteer worker* to come and care for the landlady.

*In the following month, the care worker* took care

of the landlady everyday, chatted with her and made meals for her.

Under the meticulous care

of the carer, the landlady soon recovered her health.

After recovering, the landlady went back to “work”.

*She said that she intends to save more time in the “time bank” while she is still healthy*.

Today, in Switzerland,

the use of “time banks” to support old age has become a common practice.

*At present the number of “empty-nest old people”* in Asian

countries are increasing and it has gradually

become a social problem.

*Switzerland style “time bank” pension may be a good option for India too.*

*Time bank address the challenges of an aging population in the country and the increasing need for social support as the family support is dwindling.*🌷

This is Why Swiss Time Bank is a fantastic idea. is Going Viral !

Below is a detailed overview of the protections offered under the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (MHA), Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (RPwD), and Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, 2007 in India, along with guidance on how neighbors can seek help from a magistrate to address cruelty by family members, assign a limited guardian, and arrange for regular follow-up and family therapy to prevent further cruelty. Since the query seems to focus on the Indian legal context, I’ll frame the response accordingly.

1. Protections under the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 (MHA)

The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017 is a progressive, rights-based legislation in India aimed at protecting and promoting the rights of persons with mental illnesses (PMI). Key protections include:

- Right to Dignity and Non-Discrimination (Section 21): Every person with a mental illness has the right to live with dignity and be protected from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment in any mental health establishment. They are entitled to equality and non-discrimination, similar to those with physical illnesses.

- Right to Safe and Hygienic Environment: PMIs have the right to a safe and hygienic environment, privacy, and access to rehabilitation services, community living, and medical records.

- Protection from Cruel Treatment: The Act explicitly prohibits practices like electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for minors and restricts its use for adults to cases with muscle relaxants and anesthesia. It also bans seclusion and restraint unless absolutely necessary and authorized.

- Advance Directives and Nominated Representatives (Sections 5-12): PMIs can make advance directives to specify their preferred treatment and appoint a nominated representative to make decisions if they lose capacity. This ensures autonomy and supported decision-making.

- Access to Mental Health Services: The Act mandates access to mental health services, including treatment, rehabilitation, and community-based care, to promote integration and recovery.

- Role of Authorities: The Act establishes Central and State Mental Health Authorities to regulate mental health facilities and ensure compliance with rights-based provisions. It also defines the role of police and magistrates in cases of wandering or neglected PMIs, allowing intervention to ensure care and protection.

Relevance to Cruelty by Family Members: If a person with a mental illness is being subjected to cruelty (physical, emotional, or neglect) by family members, the MHA provides mechanisms to intervene. An Approved Mental Health Professional (AMHP) can apply to a magistrate under Section 135(1) of the Mental Health Act, 1983 (referenced for procedural analogy, as Indian MHA aligns with similar principles) to remove the person to a place of safety for assessment and protection if there’s reasonable cause to suspect ill-treatment or neglect.

2. Protections under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 (RPwD)

The RPwD Act, 2016 aims to protect and promote the rights of persons with disabilities (PwDs), including those with mental disabilities, in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Key protections include:

- Non-Discrimination (Section 3): PwDs are entitled to equality and protection from discrimination based on disability. This includes protection from abuse, violence, or exploitation by family members or caregivers.

- Right to Home and Family (Section 9): PwDs have the right to live in the community and with their family. If family members are cruel or neglectful, the Act allows for intervention to protect the individual, including appointing a limited guardian if needed.

- Protection from Abuse and Exploitation (Section 7): The Act mandates authorities to protect PwDs from abuse, violence, or exploitation. If a PwD is being mistreated by family members, complaints can be filed with the Executive Magistrate or District Collector, who can take protective measures, including removal from the abusive environment.

- Legal Capacity and Guardianship (Section 14): The Act allows for the appointment of a limited guardian to support decision-making for PwDs who lack capacity, ensuring their autonomy is preserved as much as possible. The guardian’s role is limited to specific decisions, avoiding overreach.

- Access to Justice (Section 12): PwDs have the right to access legal remedies, including support to file complaints against abusive family members through accessible judicial processes.

Relevance to Cruelty by Family Members: If a PwD is facing cruelty, neighbors or concerned parties can report to the District Collector or Executive Magistrate, who can initiate inquiries and protective measures, such as removing the PwD from the abusive environment or appointing a limited guardian to ensure their safety and well-being.

3. Protections under the Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, 2007

The Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, 2007 provides protections for elderly individuals (aged 60 and above) to ensure their maintenance and welfare. Key provisions include:

- Right to Maintenance (Section 4): Senior citizens are entitled to maintenance (financial support, food, clothing, shelter, and medical care) from their children or legal heirs. If neglected or abandoned, they can approach a Maintenance Tribunal.

- Protection from Abuse (Section 10): The Act protects senior citizens from physical, emotional, or financial abuse by family members. Tribunals can issue eviction orders against abusive children or relatives occupying the senior citizen’s property.

- Eviction of Abusive Family Members (Section 23): If a senior citizen transfers property to children or relatives on the condition of care and they fail to provide it, the Tribunal can declare the transfer void and order eviction. This is particularly relevant for neighbors seeking to help evict cruel family members.

- Penal Provisions: Under Section 24, failure to comply with maintenance orders can lead to fines or imprisonment. Additionally, Section 25 aligns with the Indian Penal Code (IPC) sections like 323 (causing hurt), 324, 325, or 326 (grievous hurt) for violence against senior citizens.

- Right to Dignity and Care: Senior citizens have the right to live free from physical or mental abuse, including freedom from restraints used for discipline or convenience. They can manage their finances or designate a trusted person to do so.

Relevance to Cruelty by Family Members: Neighbors can approach the Maintenance Tribunal (constituted under the Act) to report abuse or neglect of a senior citizen. The Tribunal can order maintenance, evict abusive family members, and ensure the senior citizen’s safety.

4. Neighbors Seeking Help from a Magistrate

Neighbors can play a crucial role in protecting vulnerable individuals (PMIs, PwDs, or senior citizens) by seeking intervention from a magistrate. Here’s how they can proceed:

- Reporting Abuse or Neglect:

- Under MHA: If a PMI is being ill-treated or neglected, neighbors can report to an Approved Mental Health Professional (AMHP) or directly to the police, who can approach a magistrate under Section 135(1) (aligned with international standards, applicable via MHA principles) to obtain a warrant to enter premises and remove the person to a place of safety for assessment. The police must be accompanied by an AMHP and a doctor.

- Under RPwD Act: Neighbors can report abuse to the District Collector or Executive Magistrate, who can initiate an inquiry under Section 7 and take protective measures, such as removing the PwD from the abusive environment or appointing a limited guardian.

- Under Senior Citizens Act: Neighbors can file a complaint with the Maintenance Tribunal or District Magistrate, who can investigate and issue orders for maintenance, eviction of abusive family members, or protection of the senior citizen.

- Evicting Cruel Family Members:

- For senior citizens, the Maintenance Tribunal can void property transfers and order the eviction of abusive children or relatives under Section 23 if they fail to provide care.

- For PMIs or PwDs, a magistrate can issue orders to remove the individual from an abusive environment to a place of safety or alternative care setting, potentially involving Adult Protective Services or social welfare agencies.

- Filing a Complaint:

- Neighbors can submit a written complaint to the local police, District Magistrate, or Maintenance Tribunal, detailing the cruelty, neglect, or abuse observed. Supporting evidence (e.g., witness statements, photos, or medical reports) strengthens the case.

- For PMIs, the complaint may trigger an investigation by an AMHP or mental health authority. For PwDs, the District Collector may involve disability welfare officers. For senior citizens, the Tribunal directly handles such cases.

5. Assigning a Limited Guardian

- Under RPwD Act (Section 14):

- A limited guardian can be appointed by the District Court or a designated authority to support a PwD who lacks capacity in specific areas (e.g., healthcare or financial decisions). The guardian’s powers are restricted to what is necessary, preserving the PwD’s autonomy as much as possible.

- Neighbors or concerned parties can petition the District Court or Executive Magistrate, providing evidence of the PwD’s incapacity (e.g., medical reports) and the need for guardianship due to abuse or neglect.

- The court ensures the guardian acts in the PwD’s best interests and may require regular reports.

- Under MHA:

- The MHA allows for a nominated representative (Section 14) to make decisions for a PMI if they lose capacity. This can be a trusted individual chosen by the PMI or appointed by a court. Unlike a full guardian, the representative’s role is limited to mental health decisions.

- If no representative is nominated, neighbors can request a mental health authority or magistrate to appoint one to protect the PMI from cruelty.

- Under Senior Citizens Act:

- Senior citizens can designate a guardian or representative to manage their affairs if incapacitated (e.g., via a power of attorney or court-appointed guardian). If abuse is reported, the Tribunal or court may appoint a guardian to ensure their safety and financial management.

Process:

- File a petition with the District Court, Executive Magistrate, or Maintenance Tribunal, specifying the need for a limited guardian due to cruelty or neglect.

- Provide medical or psychological assessments to establish incapacity (for PMIs or PwDs) or vulnerability (for senior citizens).

- The court will assess the suitability of the proposed guardian and limit their powers to specific areas (e.g., healthcare, residence, or finances).

6. Arranging Regular Follow-Up and Family Therapy

To ensure cruelty stops and the vulnerable individual’s well-being is maintained, the following steps can be taken:

- Regular Follow-Up:

- MHA: Mental health authorities or AMHPs can monitor the PMI’s situation post-intervention, ensuring they receive treatment and are not subjected to further cruelty. Regular assessments by mental health professionals are mandated.

- RPwD Act: The appointed limited guardian or disability welfare officer must submit periodic reports to the court or District Collector on the PwD’s condition, living situation, and services received. Courts may order social welfare agencies to conduct follow-ups.

- Senior Citizens Act: Maintenance Tribunals can order regular monitoring by social welfare officers or local authorities to ensure compliance with maintenance or protection orders.

- Neighbors can request the court or Tribunal to mandate follow-up visits by Adult Protective Services, disability officers, or social workers to check on the individual’s safety.

- Family Therapy:

- Courts or authorities can recommend or mandate family therapy as part of a protective order to address underlying issues causing cruelty. This is not explicitly mandated in the MHA, RPwD Act, or Senior Citizens Act but can be arranged through social welfare agencies or mental health services.

- Under the MHA, community-based mental health services may include counseling or therapy for families to promote reconciliation and prevent further abuse.

- For PwDs, the RPwD Act emphasizes rehabilitation and community living, which can include psychosocial support services like family therapy to improve family dynamics.

- For senior citizens, Tribunals can refer families to counseling services offered by NGOs or government agencies to address conflicts and ensure better care.

- Neighbors can request the court or social welfare department to involve NGOs or mental health professionals to facilitate therapy, especially if the family agrees to participate.

Implementation:

- The magistrate or Tribunal can direct local social welfare departments, mental health facilities, or NGOs to arrange therapy and follow-up services.

- Organizations like the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) or local District Disability Rehabilitation Centres (DDRCs) can provide therapy and rehabilitation services.

- Regular follow-up reports can be mandated to ensure compliance and the cessation of cruelty.

7. Practical Steps for Neighbors

- Document Evidence: Collect evidence of cruelty (e.g., visible injuries, statements from the victim, or witness accounts). Avoid direct confrontation with the family to ensure safety.

- Contact Authorities:

- For PMIs: Contact the local police or AMHP to report neglect or abuse. They can approach a magistrate for a warrant under MHA principles.

- For PwDs: Report to the District Collector or Executive Magistrate under the RPwD Act.

- For senior citizens: File a complaint with the Maintenance Tribunal or District Magistrate.

- Seek Legal Aid: Approach legal aid services (e.g., District Legal Services Authority) for assistance in filing petitions or complaints.

- Request Guardianship: Petition the court for a limited guardian if the individual lacks capacity, providing medical evidence and proposing a suitable guardian.

- Advocate for Follow-Up and Therapy: Request the court or authorities to mandate regular monitoring and family therapy through social welfare or mental health services.

- Engage NGOs: Organizations like HelpAge India, Disability Rights India, or local mental health NGOs can provide support, counseling, and advocacy.

8. Limitations and Considerations

- Legal Capacity: For PMIs and PwDs, courts prioritize the individual’s autonomy, so guardianship is limited to what’s necessary. Proving incapacity requires medical evidence.

- Family Resistance: Family members may resist eviction or therapy, requiring strong evidence and legal intervention.

- Resource Constraints: Access to mental health services, therapy, or follow-up may be limited in rural areas, necessitating coordination with NGOs or government agencies.

- Privacy and Consent: Therapy and interventions must respect the victim’s consent and privacy unless they lack capacity.

Conclusion

The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, and Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, 2007 provide robust protections against cruelty, neglect, or abuse for PMIs, PwDs, and senior citizens. Neighbors can approach a magistrate, Maintenance Tribunal, or District Collector to report abuse, seek eviction of cruel family members, appoint a limited guardian, and arrange for follow-up and family therapy. By documenting evidence, engaging legal and social welfare authorities, and advocating for protective measures, neighbors can help ensure the safety and dignity of vulnerable individuals. For further assistance, contact local legal aid services, mental health authorities, or NGOs like HelpAge India or NIMHANS.

If you need specific guidance on filing a complaint or identifying local authorities, please provide more details (e.g., location or specific circumstances), and I can tailor the response further.