From Ancient/Adi-Bharata to Modern-Mobile Bharat: India’s history as archaeological layers is a fascinating way to frame the evolution of its civilization. Each layer—Adi-Bharata (Prakrit-Pluralistic), Feudal-Bharata (Vedic-Sanskrit), ArabMughal-Bharata (Arabic-Urdu), EuroBritish-Bharata (English), and Modern Constitutional-Bharata (16+ Official Languages) —represents distinct phases with unique cultural, social, and political characteristics. Below, I’ll explore these layers, their contributions to India’s identity, and why some may foster greater pride in ancient Indian civilization than others, based on their alignment with indigenous values and achievements.

1. Adi-Bharata (Ancient/Indigenous India)

- Time Period: Prehistoric to ~600 CE (Vedic period, Mauryan Empire, Gupta Empire, etc.).

- Characteristics:

- Foundation of Indian civilization with the Indus Valley Civilization, Vedic texts, and early philosophies.

- Development of Sanskrit, the Upanishads, epics like the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and foundational scientific contributions in mathematics (zero, decimal system), astronomy (Aryabhata), and medicine (Ayurveda).

- Emphasis on dharma, spirituality, and universalist philosophies like Vedanta and Buddhism.

- Sophisticated urban planning (e.g., Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro) and trade networks.

- Reasons for Pride:

- This layer is often seen as the pinnacle of indigenous Indian achievement, with groundbreaking contributions to global knowledge systems.

- The cultural and intellectual output—spanning philosophy, science, and art (e.g., Ajanta-Ellora caves)—is viewed as a golden age, fostering a strong sense of pride in ancient India’s global influence.

- Indigenous systems of governance, education (Nalanda, Takshashila), and spirituality were self-sustaining and innovative.

- Challenges to Pride:

- Some modern critiques point to social hierarchies (early caste systems) as less inclusive, though these were fluid compared to later periods.

- Limited archaeological preservation compared to later layers can make it feel distant.

2. Feudal-Bharata (Medieval India)

- Time Period: ~600 CE–1200 CE (Post-Gupta, regional kingdoms like Cholas, Pallavas, Rajputs).

- Characteristics:

- Fragmented political landscape with powerful regional dynasties.

- Flourishing of temple architecture (e.g., Khajuraho, Chola temples), classical arts, and literature in regional languages.

- Advancements in trade (e.g., Chola maritime networks) and mathematics (e.g., Bhaskara II).

- Rise of Bhakti and Sufi movements, blending spirituality with local traditions.

- Reasons for Pride:

- Rich cultural synthesis, with regional identities strengthening India’s diversity.

- Architectural marvels and literary works (e.g., Kalidasa’s legacy, Tamil Sangam literature) reflect a vibrant civilization.

- Resilience of Indian traditions despite political fragmentation.

- Challenges to Pride:

- Political disunity made India vulnerable to external invasions.

- Rigidification of caste and feudal structures in some regions may be seen as regressive compared to Adi-Bharata’s fluidity.

- Less global influence compared to the earlier universalist philosophies.

3. ArabMughal-Bharata (Islamic Rule)

- Time Period: ~1200 CE–1857 CE (Delhi Sultanate, Mughal Empire).

- Characteristics:

- Introduction of Islamic governance, architecture (e.g., Taj Mahal, Red Fort), and Persian-influenced art and literature.

- Syncretic cultural developments, such as Urdu, Indo-Islamic architecture, and fusion in music (e.g., Hindustani classical).

- Centralized administration under Mughals, with economic prosperity (India’s GDP was ~25% of the world’s in the 16th century).

- Periods of religious tolerance (e.g., Akbar’s policies) alongside instances of conflict.

- Reasons for Pride:

- Syncretism enriched India’s cultural tapestry, with contributions like Mughal miniature paintings and Dhrupad music.

- Economic and administrative achievements under rulers like Akbar.

- Sufi and Bhakti movements fostered spiritual unity across communities.

- Challenges to Pride:

- Some view this layer as less “Indian” due to foreign origins of ruling elites, leading to debates about cultural imposition.

- Instances of religious intolerance or destruction of temples (e.g., under Aurangzeb) create mixed sentiments.

- Disconnect from the ancient indigenous traditions of Adi-Bharata, which some see as India’s “authentic” identity.

4. EuroBritish-Bharata (Colonial Period)

- Time Period: ~1757 CE–1947 CE (British East India Company and British Raj).

- Characteristics:

- Colonial exploitation, with systematic economic drain (e.g., India’s wealth reduced from 27% of global GDP in 1700 to ~4% by 1947).

- Introduction of Western institutions: railways, telegraph, English education, and legal systems.

- Cultural suppression of indigenous practices, alongside reform movements (e.g., Brahmo Samaj, Arya Samaj) inspired by Western ideas.

- Rise of Indian nationalism, culminating in the independence movement.

- Reasons for Pride:

- Resilience of Indian identity despite colonial oppression.

- Emergence of modern Indian thinkers (e.g., Tagore, Gandhi) who blended Indian and Western ideas.

- The independence struggle as a unifying force, showcasing India’s spirit.

- Challenges to Pride:

- Economic and cultural exploitation left deep scars, with famines (e.g., Bengal Famine of 1943) and deindustrialization.

- Colonial education often devalued ancient Indian knowledge systems, creating a sense of inferiority.

- This layer is least associated with pride in ancient India due to its foreign dominance and disruption of indigenous continuity.

5. Modern Constitutional-Bharata (Post-Independence India)

- Time Period: 1947 CE–Present.

- Characteristics:

- Establishment of a democratic, secular republic with the Constitution of 1950.

- Rapid modernization, technological advancements (e.g., ISRO, IT sector), and global integration.

- Revival of interest in ancient Indian heritage (e.g., yoga, Ayurveda) alongside globalized culture.

- Challenges of balancing tradition with modernity, addressing social inequalities, and fostering national unity.

- Reasons for Pride:

- India’s success as the world’s largest democracy and its global influence in technology, culture, and diplomacy.

- Rediscovery and global promotion of ancient Indian knowledge (e.g., yoga’s UNESCO recognition).

- Resilience in maintaining cultural diversity while embracing modernity.

- Challenges to Pride:

- Disconnect from ancient roots due to Westernization and globalization.

- Ongoing social issues (e.g., caste, poverty) can overshadow pride in ancient achievements.

- Some view the modern state as detached from the “glory” of Adi-Bharata’s universalist ideals.

Comparative Analysis

- Layers Most Aligned with Pride in Ancient India:

- Adi-Bharata: This layer is the most celebrated for its indigenous achievements in philosophy, science, and culture. It embodies the “golden age” narrative, with global contributions that remain influential (e.g., Buddhism’s spread, mathematical innovations).

- Feudal-Bharata: Regional pride in cultural and artistic achievements fosters a connection to ancient roots, though political fragmentation dilutes its universal appeal.

- Layers Less Aligned with Pride in Ancient India:

- ArabMughal-Bharata: While culturally rich, its foreign origins and occasional religious tensions make it less associated with indigenous pride.

- EuroBritish-Bharata: Colonial exploitation and cultural suppression distance this layer from ancient India’s legacy, though the independence movement sparks national pride.

- Modern Constitutional-Bharata: Pride is more forward-looking, focused on modern achievements. Ancient India’s legacy is selectively invoked (e.g., yoga, spirituality) but often overshadowed by contemporary challenges.

Why Some Layers Foster Less Pride

- Foreign Influence: ArabMughal and EuroBritish layers involve external rulers, which some see as diluting India’s indigenous identity. Adi-Bharata and Feudal-Bharata, being homegrown, align more with pride in ancient roots.

- Cultural Disruption: Colonial policies (EuroBritish) and, to a lesser extent, religious conflicts (ArabMughal) disrupted continuity with ancient traditions, unlike the organic evolution of Adi-Bharata.

- Modern Disconnect: Modern Constitutional-Bharata prioritizes global integration, which can feel detached from ancient India’s spiritual and intellectual ethos.

- Historical Narratives: Nationalist historiography often glorifies Adi-Bharata as a high point, while later layers are critiqued for invasions or exploitation, shaping perceptions of pride.

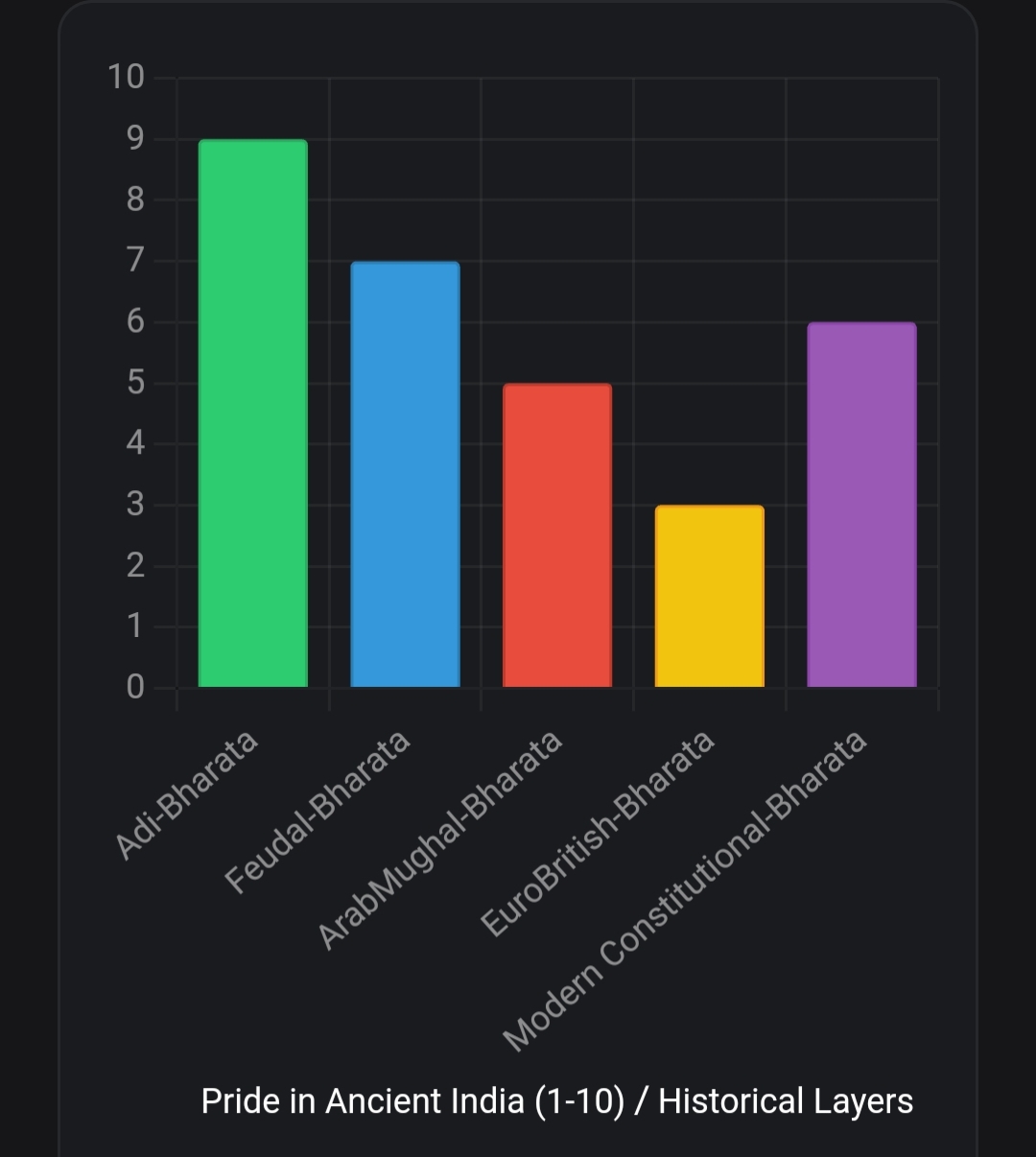

Visualizing the Layers (Chart)

To illustrate the relative pride in ancient India across these layers, here’s a chart representing their perceived connection to ancient Indian civilization (based on cultural continuity and indigenous contributions). The y-axis represents the “Pride in Ancient India” (on a scale of 1–10, subjective estimation), and the x-axis lists the layers.{ "type": "bar", "data": { "labels": ["Adi-Bharata", "Feudal-Bharata", "ArabMughal-Bharata", "EuroBritish-Bharata", "Modern Constitutional-Bharata"], "datasets": [{ "label": "Pride in Ancient India", "data": [9, 7, 5, 3, 6], "backgroundColor": ["#2ecc71", "#3498db", "#e74c3c", "#f1c40f", "#9b59b6"], "borderColor": ["#27ae60", "#2980b9", "#c0392b", "#f39c12", "#8e44ad"], "borderWidth": 1 }] }, "options": { "scales": { "y": { "beginAtZero": true, "max": 10, "title": { "display": true, "text": "Pride in Ancient India (1-10)" } }, "x": { "title": { "display": true, "text": "Historical Layers" } } }, "plugins": { "legend": { "display": false } } } }

This chart reflects the subjective assessment that Adi-Bharata inspires the most pride due to its indigenous achievements, followed by Feudal-Bharata. ArabMughal and EuroBritish layers rank lower due to foreign influence, while Modern Constitutional-Bharata balances pride in heritage with modern identity.

Conclusion

The layers of Adi-Bharata and Feudal-Bharata are most likely to evoke pride in ancient India due to their deep roots in indigenous culture, intellectual achievements, and global influence. ArabMughal and EuroBritish layers, while contributing to India’s syncretic identity, are less associated with ancient pride due to foreign dominance and disruption. Modern Constitutional-Bharata bridges past and present but often prioritizes contemporary achievements over ancient legacy. Each layer, like an archaeological stratum, reveals a complex interplay of continuity and change, shaping India’s multifaceted identity. If you’d like me to delve deeper into any layer or aspect (e.g., specific contributions, archaeological evidence), let me know!