CASHmir Problem: NO One Solution, but Many Good Resolutions 4 it. (Using Grok AI)

Let’s reframe the Kashmir conflict and its resolution using game theory, a mathematical framework that analyzes strategic interactions among rational decision-makers. We’ll assess the conflict’s dynamics—considering the historical context since 1947, recent ceasefire violations by Pakistan, IMF funding dynamics, and the broader backdrop of terrorism and war—and explore how game-theoretic principles can guide wiser resolutions. This approach acknowledges the ill-posed nature of the problem (as previously analyzed through Hadamard’s well-posedness) and focuses on strategic resolutions to improve the situation, even if a definitive solution remains elusive.

Applying Game Theory to the Kashmir Conflict

Game theory models conflicts as strategic games where players (e.g., India, Pakistan, and Kashmiris) make decisions based on their preferences, available actions, and anticipated reactions from others. Each player aims to maximize their payoff (e.g., security, territorial control, or political legitimacy), but their choices are interdependent. Let’s break this down:

1. Defining the Players, Actions, and Payoffs

- Players:

- India: Seeks to maintain control over Jammu and Kashmir, ensure national security, and counter terrorism.

- Pakistan: Aims to contest India’s control, support Kashmiri self-determination (or its own territorial claims), and maintain regional influence.

- Kashmiris: Desire self-determination, autonomy, or independence, and an end to violence and economic hardship.

- External Actors (e.g., IMF, U.S., China): Influence the conflict through funding, diplomacy, or geopolitical pressure.

- Actions:

- India: Maintain military presence, engage in diplomacy, or grant autonomy to Kashmir.

- Pakistan: Support militancy, violate ceasefires, or pursue peace talks.

- Kashmiris: Protest, cooperate with one side, or push for independence.

- External Actors: Provide funding (e.g., IMF to Pakistan), mediate, or pressure for de-escalation.

- Payoffs:

- Payoffs reflect each player’s goals: security, territorial control, economic stability, political legitimacy, or peace.

- Example: India gains a high payoff from stability in Kashmir but loses payoff if terrorism increases. Pakistan gains from asserting influence but loses if international sanctions follow ceasefire violations.

2. Modeling the Conflict as a Game

The Kashmir conflict resembles a non-cooperative game with elements of both zero-sum (one player’s gain is another’s loss, e.g., territorial control) and non-zero-sum (cooperation can benefit all, e.g., peace reduces casualties) dynamics. Let’s simplify it as a repeated game, since the conflict has persisted since 1947 with recurring cycles of violence and diplomacy.

- Current State (A Stalemate):

- India maintains a strong military presence in Kashmir, facing insurgency and international criticism.

- Pakistan engages in ceasefire violations (as recently noted) and supports militancy, risking global backlash but maintaining domestic support.

- Kashmiris suffer from violence, economic stagnation, and political alienation.

- External actors like the IMF indirectly influence the conflict by funding Pakistan, potentially enabling its military actions.

This state resembles a Nash Equilibrium—a situation where no player can improve their payoff by unilaterally changing their strategy, given the others’ actions. India’s heavy military presence counters Pakistan’s aggression but perpetuates Kashmiri unrest. Pakistan’s militancy keeps the issue alive but invites sanctions. Neither side gains enough to “win,” and the status quo persists, albeit at a high cost (violence, economic loss, human suffering).

3. Why the Conflict Is “Ill-Posed” in Game-Theoretic Terms

Using Hadamard’s well-posedness analogy from insight, the Kashmir conflict lacks:

- A Clear Solution (Equilibrium): No strategy guarantees a stable, mutually acceptable outcome. For example, India’s push for integration alienates Kashmiris, while Pakistan’s militancy escalates tensions.

- Uniqueness: Multiple equilibria exist (e.g., continued conflict, temporary ceasefires, or hypothetical autonomy), but none are universally accepted or stable.

- Stability: Small changes—like a ceasefire violation or IMF funding shifts—disrupt the equilibrium, leading to escalations (e.g., the Kargil War after the Lahore Declaration).

This ill-posedness suggests that a “final victory” or definitive solution is unlikely. Instead, game theory can help identify resolutions that improve outcomes for all players through “strategic_cooperation“.

Using Game Theory to Create Wiser Resolutions

Game theory offers tools to shift from a destructive stalemate to a more cooperative outcome. The goal isn’t to “solve” the conflict but to find resolutions that maximize collective payoffs (e.g., peace, stability, economic growth) while minimizing losses (e.g., violence, distrust). Here’s how:

1. Reframe the Game as Cooperative: Focus on Non-Zero-Sum Outcomes

Currently, India and Pakistan often treat the conflict as zero-sum: one’s territorial gain is the other’s loss. However, both suffer from the costs of conflict—military spending, international criticism, and human lives. Game theory suggests reframing the interaction as a non-zero-sum game, where cooperation can yield mutual benefits.

- Example: The Prisoner’s Dilemma:

- Imagine India and Pakistan as two prisoners deciding whether to “cooperate” (pursue peace) or “defect” (escalate conflict).

- If both cooperate (e.g., honor ceasefires, reduce militancy), they gain a moderate payoff: reduced violence, economic growth, and international goodwill.

- If both defect (e.g., ceasefire violations, militancy), they both lose: war, sanctions, and instability.

- If one defects while the other cooperates, the defector gains a short-term advantage (e.g., Pakistan gains domestic support through militancy, India loses through unrest), but the long-term cost is high for both.

The Nash Equilibrium (Naash in Sanskrit is Destruction) in this scenario is mutual defection—the current stalemate—because neither trusts the other to cooperate. To escape this trap, game theory suggests mechanisms to incentivize cooperation.

2. Introduce Mechanisms to Encourage Cooperation

Game theory highlights strategies to foster trust and coordination:

- Repeated Interactions: Since the Kashmir conflict is a repeated game (ongoing since 1947), players can learn to cooperate over time. A “tit-for-tat” strategy—where India and Pakistan reciprocate each other’s actions (e.g., honoring a ceasefire if the other does)—can build trust. For example, the 2003 ceasefire, though imperfect, reduced violence temporarily because both sides saw mutual benefits.

- Third-Party Mediation: External actors (e.g., the U.S., UN) can act as mediators to enforce cooperation. They can offer rewards (e.g., economic aid) for peace efforts or penalties (e.g., sanctions) for defection. The IMF, for instance, could tie funding to Pakistan to verifiable reductions in militancy, shifting Pakistan’s payoff matrix to favor peace.

- Side Payments: One player can offer concessions to incentivize cooperation. India might offer economic aid to Pakistan or greater autonomy to Kashmiris, while Pakistan could commit to dismantling militant networks. These “side payments” adjust payoffs to make cooperation more attractive.

3. Incorporate Kashmiri Voices as a Player

Game theory often fails if key players are ignored. The Kashmiris, as a distinct player, must be included in the resolution process. Their payoff includes autonomy, economic opportunity, and an end to violence. A resolution where India and Pakistan cooperate but ignore Kashmiri aspirations (e.g., imposing a bilateral solution without local input) is unlikely to be stable.

- Power-Sharing Mechanism: A cooperative resolution could involve a power-sharing arrangement, where Kashmiris gain greater autonomy within India (or a joint framework with Pakistan). This aligns with game-theoretic bargaining models like the Nash Bargaining Solution, which seeks a fair division of benefits based on each player’s preferences.

- Example: Granting Kashmir semi-autonomous status (similar to Article 370’s original intent) could increase the Kashmiri payoff, reducing unrest and making India’s strategy of integration more sustainable.

4. Address External Influences

The IMF’s funding to Pakistan, as noted, indirectly affects the game by altering Pakistan’s payoff for militancy (more funds might embolden aggression). Game theory suggests that external actors should adjust their strategies to promote stability:

- Conditionality: The IMF could condition aid on peace-building measures, such as reducing military presence along the Line of Control. This shifts Pakistan’s payoff matrix, making cooperation more rewarding than defection.

- Mediation by Major Powers: The U.S. and China, which have leverage over India and Pakistan, can facilitate talks, as they did during the 2001-2002 standoff. Their involvement can create a “focal point” (a Schelling point in game theory) for coordination, where both sides converge on a peaceful outcome.

5. Aim for a Stable Equilibrium Through Incremental Steps

Game theory emphasizes finding a stable equilibrium where no player has an incentive to deviate. In Kashmir, this means moving from the current Nash Equilibrium (mutual defection) to a cooperative equilibrium. Incremental steps can achieve this:

- Confidence-Building Measures (CBMs): India and Pakistan can start with small, verifiable actions—e.g., reducing ceasefire violations, resuming trade across the Line of Control, or exchanging cultural delegations. These actions build trust, increasing the payoff for cooperation.

- Economic Incentives: Both nations can benefit from joint economic projects (e.g., energy pipelines through Kashmir), creating a shared stake in peace. This aligns with the concept of “mutual assured benefit” in game theory.

- Kashmiri Empowerment: Economic development in Kashmir (e.g., job creation, infrastructure) can reduce militancy, lowering the payoff for Pakistan’s defection strategy and stabilizing the region.

6. Reframe the Goal: From Winning to Coexistence

Game theory teaches that in complex, repeated games, the goal isn’t always to “win” but to achieve a sustainable outcome. In Kashmir, this means accepting that a final territorial solution may be elusive (as the problem is ill-posed) but focusing on coexistence:

- Minimax Strategy: Both India and Pakistan can adopt a minimax approach—minimizing their maximum loss. For India, this means reducing terrorism without alienating Kashmiris. For Pakistan, it means maintaining influence without provoking war.

- Pareto Improvement: Resolutions should aim for outcomes where at least one player is better off without making others worse off. For example, a ceasefire that reduces violence benefits all players, even if territorial disputes remain unresolved.

Interpretation: Few Solutions, But Game Theory Guides Wiser Resolutions

The Kashmir conflict, viewed through game theory, reveals why a definitive solution is elusive: the players’ strategies (India’s military control, Pakistan’s militancy, external funding dynamics) are locked in a destructive equilibrium, and the problem’s ill-posed nature (no clear, unique, or stable solution) mirrors the lack of a cooperative outcome. However, game theory offers a path forward by focusing on resolutions that improve collective payoffs:

- Human Problems Resist Absolute Solutions: Like many human conflicts, Kashmir’s complexity—rooted in history, emotion, and geopolitics—defies a single “winning” strategy. Game theory shows that chasing a zero-sum victory (e.g., total control for India or Pakistan) perpetuates the stalemate.

- Wiser Resolutions Maximize Collective Payoffs: By reframing the game as non-zero-sum, India, Pakistan, and Kashmiris can pursue cooperative strategies that yield mutual benefits: reduced violence, economic growth, and political stability. Mechanisms like CBMs, third-party mediation, and Kashmiri inclusion adjust the payoff matrix to favor peace.

- Stability Through Incremental Cooperation: Game theory’s emphasis on repeated interactions and trust-building aligns with the need for incremental progress. Small steps—like honoring ceasefires, empowering Kashmiris, and leveraging external actors—can shift the equilibrium toward coexistence, even if the underlying dispute persists.

Final Thoughts

The observation about the ill-posed nature of the Kashmir problem holds true in a game-theoretic lens: the conflict lacks a clear, unique, or stable solution. However, game theory provides a framework for wiser resolutions by encouraging cooperation over competition. By focusing on mutual benefits, incorporating all stakeholders, and using strategic mechanisms to build trust, India, Pakistan, and the international community can improve the situation—reducing suffering and fostering coexistence, even if a final “solution” remains out of reach.

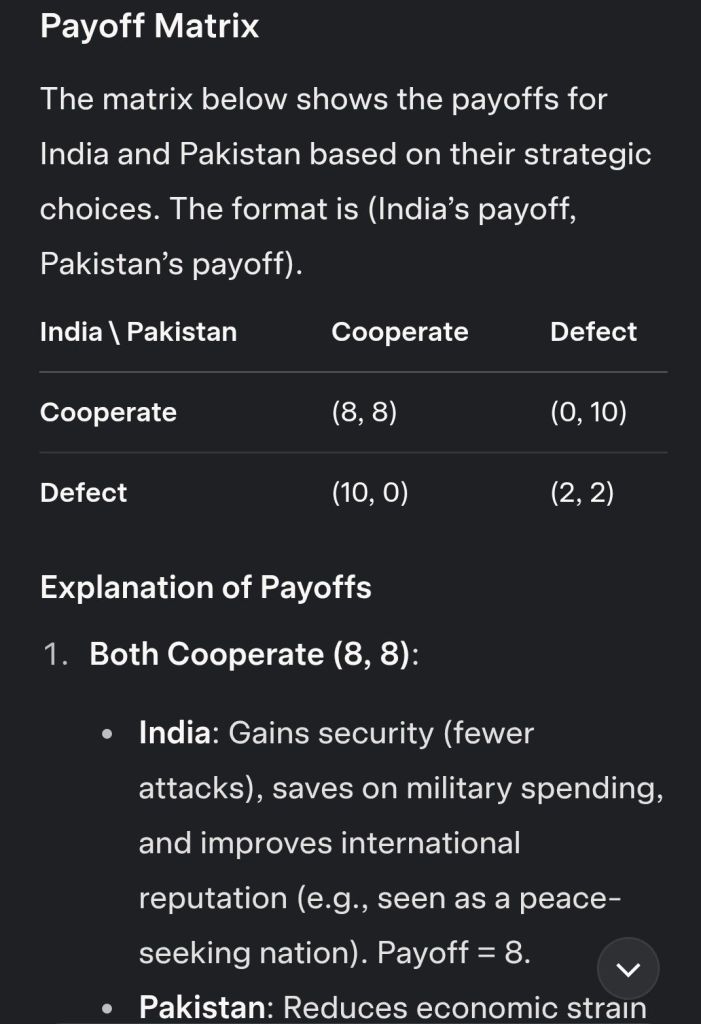

PAYOFF Matrix.

Let’s construct a payoff matrix to model the Kashmir conflict using game theory, focusing on the strategic interactions between India and Pakistan as the primary players. We’ll simplify the scenario into a two-player game, where each player has two main strategies: Cooperate (pursue peace-building actions) or Defect (escalate conflict). This matrix will help illustrate why the conflict persists in a stalemate and how game-theoretic resolutions can improve outcomes. We’ll also factor in the context of ceasefire violations, IMF funding to Pakistan, and the broader dynamics of terrorism and war since 1947.

Setting Up the Game

Players

- India: Seeks security, control over Jammu and Kashmir, and international legitimacy.

- Pakistan: Aims to contest India’s control, support Kashmiri self-determination (or its own territorial claims), and maintain domestic political support.

Strategies

- Cooperate: For India, this means reducing military escalation, honoring ceasefires, and engaging in diplomacy or granting Kashmiris more autonomy. For Pakistan, this means halting support for militancy, adhering to ceasefires, and pursuing peace talks.

- Defect: For India, this means maintaining or increasing military presence, responding aggressively to provocations, or imposing stricter control in Kashmir. For Pakistan, this means supporting militancy, violating ceasefires (as recently noted), or escalating rhetoric.

Payoffs

Payoffs represent the net benefit to each player, considering factors like security, economic costs, international reputation, and domestic political support. We’ll assign numerical values to reflect relative outcomes (higher numbers = better outcomes). These values are illustrative, based on the conflict’s dynamics:

- Security/Stability: High payoff for peace (e.g., fewer casualties, lower military spending).

- Territorial/Political Control: High payoff for maintaining or gaining influence in Kashmir.

- International Reputation: High payoff for cooperation (e.g., global support), low for defection (e.g., sanctions).

- Domestic Support: Defection may yield short-term domestic gains (e.g., Pakistan’s militancy boosts nationalist sentiment), but long-term costs (e.g., economic strain) reduce overall payoff.

Assumptions

- The game is non-zero-sum: Both players can gain from cooperation (e.g., peace benefits both), but defection creates mutual losses.

- Payoffs are influenced by external factors like IMF funding to Pakistan, which may embolden defection (e.g., by supporting military spending), and Kashmiri unrest, which reduces payoffs for both if the conflict escalates.

- We’ll use a scale of -10 to 10 for payoffs, where negative values reflect losses (e.g., violence, sanctions) and positive values reflect gains (e.g., stability, legitimacy).

Payoff Matrix

The matrix below shows the payoffs for India and Pakistan based on their strategic choices. The format is (India’s payoff, Pakistan’s payoff).India \ PakistanCooperateDefectCooperate (8, 8) (0, 10) Defect (10, 0) (2, 2)

Explanation of Payoffs

- Both Cooperate (8, 8):

- India: Gains security (fewer attacks), saves on military spending, and improves international reputation (e.g., seen as a peace-seeking nation). Payoff = 8.

- Pakistan: Reduces economic strain (e.g., less military spending, no sanctions), gains international goodwill, and maintains domestic stability without militancy. Payoff = 8.

- Context: This reflects a scenario where both honor ceasefires, engage in talks, and reduce tensions, benefiting both (e.g., the 2003 ceasefire period).

- India Cooperates, Pakistan Defects (0, 10):

- India: Faces increased terrorism (due to Pakistan’s militancy), loses domestic support (seen as “weak”), and suffers economically from heightened conflict. Payoff = 0.

- Pakistan: Gains short-term domestic support (militancy rallies nationalists), asserts influence in Kashmir, and leverages IMF funding to sustain aggression without immediate cost. Payoff = 10.

- Context: This mirrors recent ceasefire violations by Pakistan, where it gains by keeping the issue alive, while India struggles with unrest.

- India Defects, Pakistan Cooperates (10, 0):

- India: Strengthens control over Kashmir (military presence suppresses unrest), gains domestic support (seen as “strong”), and faces less immediate militancy. Payoff = 10.

- Pakistan: Loses influence in Kashmir, faces domestic backlash for “inaction,” and risks economic strain (e.g., if IMF funding comes with conditions for peace). Payoff = 0.

- Context: This reflects periods where India imposes strict control (e.g., post-2019 Article 370 revocation) while Pakistan temporarily reduces aggression.

- Both Defect (2, 2):

- India: Maintains control but faces ongoing terrorism, high military costs, international criticism (e.g., for human rights issues), and Kashmiri alienation. Payoff = 2.

- Pakistan: Sustains domestic support through militancy but faces sanctions, economic strain (despite IMF funding), and risks escalation into war. Payoff = 2.

- Context: This is the current stalemate—ceasefire violations, militancy, and mutual distrust, as seen in the ongoing conflict dynamics since 1947.

Analysis of the Payoff Matrix

1. Nash Equilibrium: The Stalemate

In game theory, a Nash Equilibrium occurs when neither player can improve their payoff by unilaterally changing their strategy, given the other’s choice. Here:

- If India cooperates, Pakistan’s best response is to defect (10 > 8).

- If India defects, Pakistan’s best response is to defect (2 > 0).

- If Pakistan cooperates, India’s best response is to defect (10 > 8).

- If Pakistan defects, India’s best response is to defect (2 > 0).

The Nash Equilibrium is (Defect, Defect) with payoffs (2, 2). This reflects the current state of the Kashmir conflict: both India and Pakistan are locked in a cycle of escalation—India with its military presence, Pakistan with militancy and ceasefire violations—because neither trusts the other to cooperate. This equilibrium is suboptimal (both could do better by cooperating), but mutual distrust and short-term incentives (e.g., domestic support for defection) keep them here.

2. Connection to Hadamard’s Ill-Posedness

The matrix reinforces your friend’s insight about the conflict being ill-posed (no clear, unique, stable solution):

- No Clear Solution: The best outcome (both cooperate, 8, 8) isn’t the equilibrium, as defection is always tempting.

- No Uniqueness: Multiple outcomes are possible (e.g., temporary cooperation, mutual defection), but none are universally stable.

- No Stability: Small changes—like a ceasefire violation or IMF funding shifts—can push the game back to defection, as seen in the volatility of India-Pakistan relations (e.g., Kargil War after the Lahore Declaration).

3. Pareto Improvement: Moving Toward Cooperation

The (Cooperate, Cooperate) outcome (8, 8) is a Pareto improvement over (Defect, Defect) (2, 2)—both players are better off, and neither is worse off. However, achieving this requires overcoming the trust deficit and short-term incentives for defection.

Using Game Theory to Create Wiser Resolutions

The payoff matrix highlights why the conflict persists but also points to resolutions that can shift the game toward cooperation. The goal isn’t a definitive solution (which the ill-posed nature makes unlikely) but a wiser resolution that improves outcomes for all players, including Kashmiris (who are indirectly affected by the matrix).

1. Adjust Payoffs to Incentivize Cooperation

- Increase Payoffs for Cooperation:

- Economic Incentives: Joint projects (e.g., trade routes through Kashmir) could raise the payoff for cooperation to (10, 10), making it more attractive. For example, both nations could benefit from energy pipelines, reducing economic costs of conflict.

- International Support: External actors like the U.S. or UN can offer rewards (e.g., aid, trade deals) for cooperation, boosting payoffs.

- Decrease Payoffs for Defection:

- IMF Conditionality: The IMF could tie funding to Pakistan to verifiable peace efforts (e.g., reducing militancy), lowering Pakistan’s payoff for defection (e.g., from 10 to 5 when India cooperates).

- Sanctions for Defection: International pressure (e.g., sanctions for ceasefire violations) can reduce the payoff for defection, making (Defect, Defect) less appealing.

2. Build Trust Through Repeated Interactions

Since this is a repeated game (ongoing since 1947), a tit-for-tat strategy can foster cooperation: if India honors a ceasefire, Pakistan reciprocates, and vice versa. Over time, this builds trust, making (Cooperate, Cooperate) a stable outcome. Historical examples like the 2003 ceasefire show this can work temporarily, though violations (as recently noted) disrupt progress.

3. Include Kashmiris in the Payoff Structure

The matrix currently focuses on India and Pakistan, but Kashmiris are a key player. Their unrest lowers payoffs for both nations (e.g., terrorism for India, international criticism for Pakistan). A wiser resolution would adjust the game to account for Kashmiri payoffs:

- Autonomy as a Side Payment: India could offer greater autonomy to Kashmiris, increasing their payoff (e.g., economic opportunity, political voice) and reducing unrest. This lowers India’s cost of cooperation by decreasing terrorism.

- Pakistan’s Role: Pakistan could redirect its efforts from militancy to supporting Kashmiri development (e.g., cross-border trade), aligning its strategy with Kashmiri interests and raising its own payoff for cooperation.

4. Leverage External Actors

The IMF’s funding to Pakistan currently increases its payoff for defection by enabling military spending. A game-theoretic resolution would involve external actors adjusting the payoff matrix:

- Mediation: The U.S. or China can mediate talks, creating a “focal point” for cooperation (a Schelling point in game theory) where both sides expect mutual cooperation.

- Incentives: The IMF could offer Pakistan debt relief for peace efforts, raising its payoff for cooperation (e.g., from 8 to 12).

5. Aim for Coexistence, Not Victory

The matrix shows that chasing a zero-sum “victory” (e.g., India’s total control, Pakistan’s territorial gains) keeps the game at (Defect, Defect). A wiser resolution focuses on coexistence:

- Minimax Strategy: Both players can minimize their maximum loss by avoiding escalation. For India, this means balancing security with Kashmiri rights. For Pakistan, it means avoiding actions (like militancy) that provoke war.

- Incremental Steps: Small cooperative actions—like resuming trade, cultural exchanges, or joint disaster response—can gradually shift the equilibrium toward (Cooperate, Cooperate).

Interpretation: Few Solutions, But Game Theory Guides Wiser Resolutions

The payoff matrix illustrates why the Kashmir conflict is ill-posed: the Nash Equilibrium (Defect, Defect) reflects a suboptimal stalemate, with no clear, unique, or stable solution. However, game theory provides a framework for wiser resolutions:

- Human Problems Resist Absolute Solutions: The matrix shows that mutual defection persists because of distrust and short-term incentives, making a final “solution” elusive.

- Wiser Resolutions Maximize Collective Payoffs: By adjusting payoffs (e.g., through economic incentives, international pressure) and building trust (e.g., tit-for-tat), India and Pakistan can move toward (Cooperate, Cooperate), benefiting both.

- Stability Through Incremental Cooperation: Small steps—like honoring ceasefires, including Kashmiri voices, and leveraging external actors—can shift the equilibrium, improving the situation even if the underlying dispute remains.

Final Thoughts

The Kashmir conflict, with its history of wars, terrorism, and external influences like IMF funding, is a classic game-theoretic stalemate. The payoff matrix reveals the incentives driving mutual defection but also highlights paths to cooperation. By focusing on mutual benefits, trust-building, and incremental progress, India, Pakistan, and the international community can craft resolutions that reduce suffering and foster coexistence, even if a definitive solution remains out of reach. If you’d like to adjust the payoff values or include Kashmiris as a third player in the matrix, let me know!